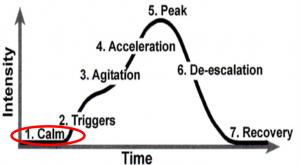

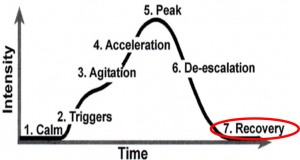

Even with a plan for preventing and responding to behavior errors, these errors will occasionally occur. To reduce the likelihood of minor behavior errors developing into major behavior events, it’s important to be familiar with the Acting Out Cycle (Colvin, 2004). Understanding the phases of the acting out cycle, including typical student behaviors at each phase, will help staff to recognize how actions or words can be used to help calm or de-escalate a situation, and what actions or words should not be used in order to avoid making the situation worse.

Phase 1 – Calm > Students exhibit expected behavior and are responsive to staff directions.

Calm is the desired state of behavior in the classroom. When expectations/rules and procedures/routines are in place, and students receive instruction, practice, and frequent, specific positive and corrective feedback, the likelihood of students operating in the calm phase is significantly increased. Consistent, predictable environments reduce variability and anxiety, resulting in more instructional time and student engagement. Consider these examples:

Travis is reading at his desk during independent work time after finishing his assignment.

Nora takes notes as the teacher explains the procedure for the lab project.

Denise listens to instructions as the teacher hands out the assignment.

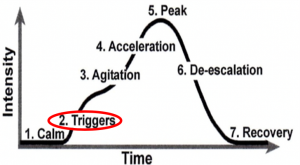

Phase 2 – Triggers > Triggers are activities, events, or behaviors that spark a behavior error.

Triggers can be related to things happening at school or outside of school. Some triggers are predictable and can be mitigated, if not avoided all together. For example, if students are hungry, they may be more irritable and find it harder to concentrate, which could contribute to behavior errors. Ensuring the student has access to breakfast and lunch at school, or even a small snack in the classroom can alleviate some of the effects of hunger as a trigger. Most triggers originating outside of school are not within the power of the school to change, but awareness and resulting proactive prevention can help.

Other triggers can be less predictable, like having a negative interaction (or perceiving a negative interaction) with a peer or adult, finding an assignment too confusing or challenging, disruption in the schedule or routine (e.g., fire drill, assembly, substitute, guest speaker), losing a personal item or assignment, feeling rushed, or other concern. Some school-based triggers can be resolved fairly easily, like changing a work group or seating arrangement, and some may require more effort or planning, such as differentiating independent work assignments or arranging for additional academic support.

Sometimes the adult in the classroom can engage in a behavior that acts as a trigger. Frequently, this will be a comment or action that is perceived negatively, though it was not intended to be so. When the adult is rushed or frustrated, this can be more likely to occur. It is also important to monitor the use of sarcasm or some types of humor in the classroom, as these can easily be interpreted in ways they were not intended. Awareness of student response is important. Consider these examples:

Travis turns around and says, “Quit,” to the student behind him.

Nora shakes her head when the teacher assigns new lab partners for the day.

Denise gets a note from the office saying she will need to ride the bus home instead of going home with a friend because she will need to watch her brother while her mom works late.

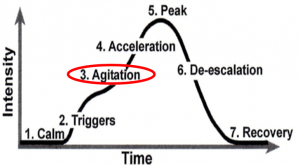

Phase 3 – Agitation > Characterized by emotional responses (e.g., anger, depression, worry, anxiety, frustration)

The agitation phase can vary in length from seconds to minutes or longer. The student may become tense, start bouncing a leg or clenching their fists, exhibit a negative facial expression, or become restless. Conversely, a student might also withdraw from the situation, look down or away, put their head down, ask to go to the restroom or nurse, or stop talking or interacting with peers or adults. In this phase, the student is beginning to get upset or frustrated, but has not necessarily started exhibiting behavior errors at this time.

To maximize the chance of de-escalating or avoiding more significant behavior errors, it is important for the adult to recognize the signs of agitation, and attempt to intervene early in the agitation phase, or even at the trigger if possible. The adult should privately and calmly talk to the student. Possible things to say could include:

“Travis, is something bothering you? Can I help?”

“Nora, I notice you seem frustrated. Is there something you need?”

“Denise, it seems like you’re upset. Is everything ok?”

Engaging in active supervision will help adults be aware of what’s happening in the classroom, and increase the likelihood of recognizing the signs of agitation. Offering a break, offering choices (e.g., work at desk or other location, order of assignments, work independently rather than in a group), and listening to the student’s concern and validating their feelings can be very effective strategies. It is critical for the adult to maintain a calm, professional, and caring demeanor when attempting to disrupt the acting out cycle.

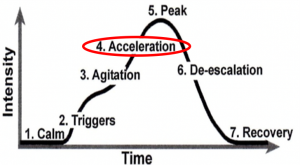

Phase 4 – Acceleration > Student engages in noticeable behavior errors, with physical responses more pronounced.

During the acceleration phase, students may be engaging in a range of behaviors that engage another person (peer or adult) in an interaction, effectively disrupting the classroom. Physical symptoms of frustration are much more apparent at the acceleration stage (e.g., sighing, head shaking, jerky movement, hyper-alertness).

This may be the first time the teacher notices there is a problem happening with the student. What the teacher does at this time is very important – often the actions of the teacher can stall the behavior errors to give the situation time to calm down, or can propel the situation directly into the next phase.

The student may be making comments to try to provoke an argument, or may disregard teacher instructions entirely; both actions frequently result in teacher frustration. When frustrated, it is easier for the teacher to find themselves drawn in to an escalating argument with the student. Consider the following example:

The student may be making comments to try to provoke an argument, or may disregard teacher instructions entirely; both actions frequently result in teacher frustration. When frustrated, it is easier for the teacher to find themselves drawn in to an escalating argument with the student. Consider the following example:

The teacher has given instructions for the students to spend 5 minutes writing out their thoughts on the assigned reading in preparation for engaging in a group discussion. The teacher notices Denise is sitting at her desk with her arms crossed. Nothing is written on the graphic organizer the teacher provided. Denise’s leg is bouncing up and down, and she’s just staring down at her desk.

The teacher approaches Denise and says, “Denise, you haven’t started your writing. There are only 3 minutes left.” Denise does not look up and continues to sit with her arms folded.

Let’s look at 2 different ways this situation can be handled – one is likely to escalate the behavior errors; one is more likely to stall and de-escalate the situation.

| Non-Example – Escalating Behavior | Example – Stalling and De-Escalating Behavior |

|

The teacher says, “Denise, you need to get going on this. You’re wasting time.” Denise looks at the teacher and rolls her eyes. The teacher says, “Hey, don’t roll your eyes. I asked to you to get to work. Now there are only 2 minutes left. If you don’t have anything written down, you won’t be prepared to participate in the discussion. That’s 5 participation points right there.” Denise says, “I don’t care. I think this is stupid,” and turns her head away from the teacher. The teacher sighs and says, “Well, this is the assignment. You don’t have to like it, but you do have to do it.” The teacher taps the paper and says, “Come on, get writing.” Denise crumples up the graphic organizer and tosses it toward the garbage. She says, “I told you it’s a stupid assignment.” She refolds her arms and looks away. The teacher says, “Well, if the assignments in here are too stupid for you, I guess you can go sit in the office and see how you like that.” The teacher writes a brief referral slip. Denise yells, “Good. I can’t wait to get out of this stupid class!” Denise kicks her desk as she walks to the door. The teacher monitors Denise and uses the intercom to let the office know a student will be arriving with a referral as she watches Denise walk down the hall. |

The teacher says, “Do you have a question about the assignment I can answer?” Denise looks at the teacher and rolls her eyes. The teacher says, “Get started by writing one sentence with your opinion about the reading. I’ll check in with you in a minute.” The teacher walks away and gives Denise time to get started. Denise writes on her paper, “I think the article was stupid.” The teacher approaches Denise and says, “Thank you for getting started. You have a clear opinion on the reading. Add a sentence or two describing what makes you think that about the article.” The teacher then walks away and gives Denise space to work. The teacher says to the class, “One more minute remaining to finish up your thoughts.” Denise writes 3 more sentences on her organizer, “There was no point spending all that time talking about the stupid pottery, like, ‘Oh, look, the people kept corn in these decorated pots,’ Who cares? It should have talked way more about their actual life, especially the kids.” The teacher approaches Denise and says, “You wrote down a good talking point. Thank you for writing down your reflection.” The teacher walks away and gives instructions for the group discussion. Denise is still quiet, but she moves to the group. She doesn’t seem to be as tense as she was earlier. The teacher looks for opportunities to give positive feedback to Denise for expected behavior, but limits interaction otherwise.

|

Though Denise is engaging in behavior that may be frustrating and feel disrespectful to the teacher, maintaining a calm, level demeanor, stating the expectation, and then walking away instead of engaging in a negative interaction will reduce the likelihood of becoming enmeshed in a disagreement. While the student is in the acceleration phase, limited interaction is recommended.

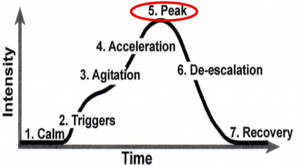

Phase 5 – Peak > Student engages in behavior that represents extreme frustration or agitation, with the possibility of causing harm to themselves, others, or property.

The peak phase is when the student exhibits the most intense behavior. This may include yelling, cursing, crying, screaming, pounding on the desk or table, ripping or destroying materials, knocking over chairs or desks, hitting, scratching, or kicking at others, or eloping from the classroom.

At this time, the primary responsibility of the teacher is to ensure the safety of the student and others. The peak phase is typically short in duration, beginning and ending abruptly. Every school should have a crisis plan which includes a section about responding to unsafe behavior in the classroom. It is important for the teacher to follow the plan, seeking assistance as directed. Some students may have individual safety plans the teacher will follow in connection to a behavior plan.

Review the peak phase from the Denise example:

nise crumples up the graphic organizer and tosses it toward the garbage. She says, “I told you it’s a stupid assignment.” She refolds her arms and looks away.

The teacher says, “Well, if the assignments in here are too stupid for you, I guess you can go sit in the office and see how you like that.” The teacher writes a brief referral slip.

Denise yells, “Good. I can’t wait to get out of this stupid class!” Denise kicks her desk as she walks to the door.

The teacher monitors Denise and uses the intercom to let the office know a student will be arriving with a referral as she watches Denise walk down the hall.

Denise’s peak phase included yelling and kicking her desk. The teacher monitored her to ensure she did not harm herself or other students, but did not attempt to engage further with her. The teacher followed the prescribed crisis plan and notified the office as directed in the plan.

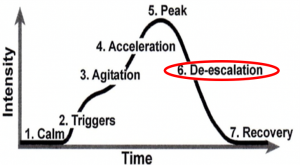

Phase 6 – De-escalation > This phase is characterized by student disengagement and reduced acting-out behavior.

The de-escalation phase occurs when the peak phase has concluded. At this time, the teacher and others will work to accomplish two things – first, restore the classroom environment and resume instruction; second, facilitate the return of the target student to the classroom.

When the peak behavior has concluded, the student may appear drained or deflated. The student may try to make excuses, become withdrawn, refuse responsibility, or try to apologize or “fix” things. Likely, the student is not ready to have a conversation about the behavior right away, but will benefit from a brief “cooling off” period. This could occur in or out of the classroom, depending on the circumstances, but the focus should remain on restoring the environment and preparing the student to successfully rejoin the class. The student is likely to be receptive to short, clear directions like:

“Come and sit down at the back table while I get you some paper so you can write down your thoughts.”

“Come and sit down at the back table while I get you some paper so you can write down your thoughts.”

Giving the student a task to focus on, like journaling, will give the teacher the opportunity to restore the environment. As the student is cooling down, the teacher will refocus the class and engage the rest of the students in a task that will allow the teacher to facilitate the student’s return to instruction. After a brief (2-3 minute) period, the teacher can help the student return to instruction.

During the recovery phase, the student will likely not be eager to talk about the incident, but it is important for the teacher to guide the student through a process of debriefing. When the student is calm, the teacher may choose to address the behavior with the student in a problem-solving way.

Phase 7 – Recovery > This phase includes brief discussion of the incident, and making a plan to move forward.

In Denise’s case, where the behavior escalated to the peak phase, and the student has left the classroom, the teacher will refocus the remainder of the class, and then work with the office to have Denise return to class. The teacher will follow the procedure for returning the student from the office to the classroom. This includes acknowledging the incident with the class, and setting the tone for the student to return to instruction. To the class, the teacher might say,

“I wish that had gone differently. As we get back to work, we need to remember that when Denise returns, she may still be upset, or feel embarrassed. Anyone can have an experience where they regret saying or doing something. It’s important for us to remember that and think about how to do things differently in the future.

When Denise comes back to the room, the teacher will take the opportunity to debrief.

“Denise, we need to talk about what happened, and I know it might be uncomfortable, but we want to figure out how to best handle situations like this. I think there are maybe some pieces missing that could help us make sense of it.”

“When I came over and asked you to get started, I was surprised by your response. Was something going on that I missed? I thought maybe you were just thinking or having trouble getting started, and wanted you to be ready for the discussion.”

Denise may say, “I was mad about the note I got about riding the bus, and couldn’t concentrate on the writing. I didn’t even see you come over until you said something, and then it just made me feel like you were saying I wasn’t working on purpose.”

The teacher may respond, “I see. I guess I didn’t realize the note you got was bothering you. When you ignored me and rolled your eyes, it felt disrespectful to me because I just thought I was giving you a prompt for time. Then when you said it was stupid, that really bothered me. I wonder what we could have done instead. Let’s get back to work now, and we can think about this more at the end of class.

When Denise returns to instruction, even with limited participation, at the end of class the teacher might say, “Denise, I appreciate that you took part in the discussion. I know you were frustrated near the beginning of class, but you did what I asked and then turned it around. You mentioned the note you got about the bus was bothering you. Do you want to talk about that?”

If the student declines to share, the teacher can say:

“People get upset sometimes. Let me know if I can help you when you feel that way. I want to be sure we avoid situations like we had today by working together to solve problems. Let me know if I can help.”

If the student responds, the teacher can listen to the student, and offer a suggestion, if appropriate. For example:

Denise responds, “I had plans to go to Maria’s house after school, but now I have to go home and babysit. This just sucks.”

Denise responds, “I had plans to go to Maria’s house after school, but now I have to go home and babysit. This just sucks.”

The teacher nods and says, “I get it, that’s disappointing when your plans get changed and it’s not your decision. I missed that you were upset about that. When something happens and you feel frustrated or upset in class, it can make concentrating on your work challenging. You successfully worked through it, though, and got your work done. Let me know if I can help you when you feel that way. I want to be sure we avoid situations like we had today by working together to solve problems. I hope you can make another plan with Maria.”

This phase can be challenging for the teacher, who may still be feeling upset or frustrated. It is important to remember behavior serves a purpose, and it’s not a personal attack, even if it feels that way. The goal is to restore and retain a safe and supportive learning environment, and the teacher will be the leader in making that happen. Restoring relationships with the class and with the student who engaged in the behavior is a critical component of maintaining the learning environment.